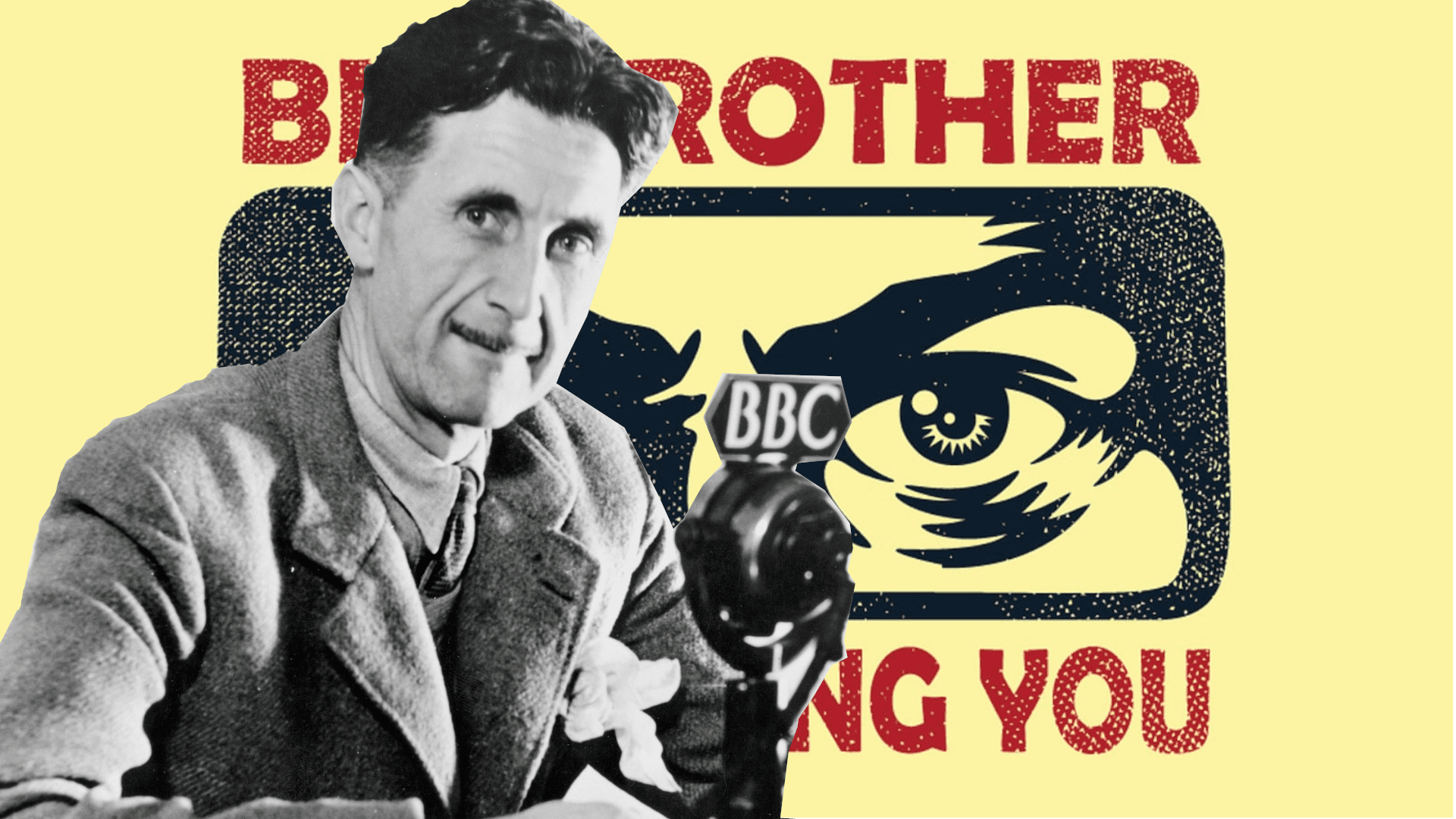

“Politics and the English Language” is a warning from George Orwell about the political dangers of bad writing. It is as urgent now as the day it was written. George Orwell (1903-1950), born Eric Arthur Blair, was one of the foremost political writers of the 20th century. Most famous for his novels 1984 and Animal Farm, Orwell was also a noted essayist. Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language,” first published in 1946, has become a classic work on the the dangerous consequences of lazy writing.

The popular use of language has always been imprecise. People (and especially politicians) like to hide their intent in fuzzy and deceptive words. But the problem affects everyone, even the most honest. We all find ourselves incapable of speaking (or writing) our full meaning.

Doing so requires self-reflection, patience, and effort. You need to find the right words and order them in a way that won’t obscure for your listener (or for you) what you want to express. This is hard.

In “Politics and the English Language,” George Orwell points out that language is decaying because we suffer from “mental vices” that encourage us to think imprecisely.

Before we get to these specific vices, we should outline the general problem.

Cliches are the easy way out

Orwell opens by stating the gravity of the situation. But he also implies that we can fix it:

Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it. Our civilization is decadent and our language—so the argument run—must inevitably share in the general collapse. It follows that any struggle against the abuse of language is a sentimental archaism, like preferring candles to electric light or hansom cabs to aeroplanes. Underneath this lies the half-conscious belief that language is a natural growth and not an instrument which we shape for our own purposes.

How can we use language as an instrument? Much later in the essay, Orwell writes, “What is above all needed is to let the meaning choose the word, and not the other way about.”

Precise thinking is tough, and it’s rare. Because you have to think precisely to write well, good writing is also tough and rare.

When I neglect to do the difficult work of thinking clearly (which, if I’m being honest, is almost always), language furnishes me with a kind of prosthetic. This prosthetic is composed of ready-made phrases, tired metaphors that have lost their power, and common idioms. It’s composed, in other words, of cliches. Instead of reaching into myself and withdrawing, thought by thought, the right way of making my point to you, I use the prosthetic. I wag its limp fingers in the direction of where we want to go. We can both see the place and assume we know what it’s like, so we don’t bother take the trip.

Which isn’t harmless, but it’s mostly fine. Like if I’m greeting an acquaintance at the grocery store. He doesn’t really want to know how I’m doing, and I don’t really think he’s lost a ton of weight. Or if I’m on a date and telling her why I like the Final Destination movies so much. She deserves a free dinner for pretending to listen to me yap—and since her thoughts are elsewhere, it doesn’t much matter what I say.

But when Orwell tells us that the decline of language is both an indication and a cause of social decay, he’s right.

The Decline of Language

“An effect,” writes Orwell, “can become a cause, reinforcing the original cause and producing the same effect in an intensified form, and so on indefinitely.”

Orwell uses drinking as an example. Say you’ve had a day that kicked your teeth in. You could use a drink, you think, so you take one. Then you take a few more, then a lot more. You wake up parched, with a headache and joints that creak with pain at even faint movements. You look at the clock—you’ve overslept. You’re an hour late for work, and things go downhill from there.

So that night you take a drink, because you need one, and you keep this going for a few weeks, then a few years, and you’re at the point where you can’t really go an evening without drinking. Your performance at work suffers, and you drink to keep the stress at bay.

But your work suffers because you drink.

So the effect and cause become interchangeable. They start to blur like a drunk’s vision.

Orwell says that language works the same way. “It becomes ugly and inaccurate because our thoughts are foolish, but the slovenliness of our language makes it easier for us to have foolish thoughts.”

Human beings, especially in groups, can be very dangerous when they’re not using their brains.

Orwell’s “Politics and the English Language” offers four techniques that lazy writers use to avoid the chore of thinking.

1. Dying metaphors

“A newly invented metaphor,” Orwell writes, “assists thought by evoking a visual image.” A “dead” metaphor doesn’t—it has “in effect reverted to being an ordinary word.”

If we speak of someone’s “iron will” to express unusual determination, or say somebody has a “soft touch” if they deal with a combustible situation in a gentle manner, we’re not saying much at all. “Iron” is used so often next to “will,” “soft” next to “touch” in these contexts that the metaphors themselves are useless. “He was determined” or “she was kind” say the same things. Metaphors are supposed to provoke a reaction, to be a catalyst for the reader to imagine how deeply determined he was, how selflessly kind she was. Dead metaphors leave the reader unmoved.

But some phrases, neither newborn or dead, are terminal. They’re on the way out, but they haven’t yet gone to that great dictionary in the sky. These are dying metaphors. A dying metaphor, Orwell says, is one that has “lost all evocative power” and is employed to “save people the trouble of inventing phrases for themselves.” He writes:

Examples are: Ring the changes on, take up the cudgels for, toe the line, ride roughshod over, stand shoulder to shoulder with, play into the hands of, no axe to grind, grist to the mill, fishing in troubled waters, on the order of the day, Achilles’ heel, swan song, hotbed. Many of these are used without knowledge of their meaning (what is a ‘rift’, for instance?), and incompatible metaphors are frequently mixed, a sure sign that the writer is not interested in what he is saying. Some metaphors now current have been twisted out of their original meaning without those who use them even being aware of the fact. For example, toe the line is sometimes written as tow the line. Another example is the hammer and the anvil, now always used with the implication that the anvil gets the worst of it. In real life it is always the anvil that breaks the hammer, never the other way about: a writer who stopped to think what he was saying would avoid perverting the original phrase.

2. Operators, or verbal false limbs

What Orwell means here is the use of extra words and syllables instead of simple verbs. He gives examples of using “render inoperative” and “militate against” when “break” or “stop” would do. The simplicity is discarded in favor of complication, because it sounds (to a shallow listener) more sophisticated.

For single verb—”such as break, stop, spoil, mend, kill”—these operators substitute a phrase. Often, too, the passive voice supplants the active. So, instead we get being rendered nonfunctional, having been made to cease, with signs of ripeness no longer visible, its brokenness rectified, and rendered dead through malice. These are exaggerations, but we’re all guilty of language nearly as clumsy. Orwell continues:

Simple conjunctions and prepositions are replaced by such phrases as with respect to, having regard to, the fact that, by dint of, in view of, in the interests of, on the hypothesis that; and the ends of sentences are saved from anticlimax by such resounding commonplaces as greatly to be desired, cannot be left out of account, a development to be expected in the near future, deserving of serious consideration, brought to a satisfactory conclusion, and so on and so forth.

3. Pretentious diction

Orwell identifies four kinds of pretentious diction, and shows why a writer (intentionally or not) might employ “elevated” forms of expression when simple prose would work better.

First, we have words that hide bias behind “an air of scientific impartiality.” He lists the following: “phenomenon, element, individual (as noun), objective, categorical, effective, virtual, basic, primary, promote, constitute, exhibit, exploit, utilize, eliminate, [and] liquidate.” Let’s imagine a newspaper headline:

ANTI-DEMOCRATIC SPIRIT ELIMINATED AS TERRORIST CELL NEUTRALIZED

And, below that, this paragraph:

In an effective bid at promoting freedom abroad, our peacekeeping forces worked with the small nation’s new government to liquidate the terrorist forces opposing the recent reforms.

On the surface, this is a good news. A terrorist cell opposing the democratic spirit in this little country was “rendered inoperative,” to use a phrase listed above. But if I think a bit about what’s being said, and who’s saying it, and matters become ambiguous at best.

Presumably, we’re seeing an article from the newspaper of a bigger, more powerful country. We don’t know anything about the “reforms” the smaller nation’s government has implemented—but we do know that big countries bully smaller ones, exploiting their resources and setting up puppet regimes to do their bidding. So maybe the “reforms” help the richer nation at the expense of the poorer one. And maybe these “terrorists” were freedom fighters who were trying to take their country back.

Then again, maybe not. Maybe the little nation had just emerged from a dictatorship, and the larger country, in a good-faith effort to gain an ally in the region, was helping the new government establish stability in a land devastated by poverty and war.

From the short sample above, we can’t determine the truth. But “promoting freedom abroad” could be a euphemism for “invade,” depending on whether the new government is a legitimate one. And “neutralize” and “liquidate” are stand-ins here for “destroy” and “kill.” If the author feels the need to soften the truth, we ought to ask why.

4. Meaningless words

“In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism,” Orwell writes, “it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning.” Among most egregious transgressors are the authors of so many “postmodern” academic papers.

In 1996, professor Andrew C. Bulhak of Monash University created a “postmodernism generator.” Here is a modified version. Visit it, and the program will generate a postmodern paper for you, including citations.

Using the program, I got a paper entitled “Capitalist Theories: Sontagist camp and neodialectic construction.”

A sample:

1. Pretextual appropriation and the deconstructive paradigm of expression

If one examines Sontagist camp, one is faced with a choice: either reject the deconstructive paradigm of expression or conclude that narrative comes from the collective unconscious. However, the premise of postconceptualist objectivism suggests that class has objective value, given that culture is interchangeable with art.

Bulhak offers insight into “meaningless words” when he tells us why he chose to “generate travesties of papers on postmodernism, literary criticism, cultural theory and similar issues.” It is “because of the combination of the complex, opaque jargon used in these sorts of works and the subjectivity of the discipline.” He says he’d have less success with math or physics papers because, although they also employ complex and opaque jargon, these fields possess a scientific rigor that the others do not.

Like some postmodern writers, many politicians use empty jargon, relying on the subjectivity of the listener to fill in the meaning. “The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice,” Orwell writes, “[…] are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different.”

Politics and the English Language

This invasion of one’s mind by ready-made phrases […] can only be prevented if one is constantly on guard against them, and every such phrase anaesthetizes a portion of one’s brain.

Earlier, we explored the idea that the use of ready-made phrases was a means to avoid thinking. Thinking is as difficult as it is necessary, so it’s painful to realize how rarely I do it. It wounds my self-image—I’d tell you, if you asked me, that I think for myself. But even “think for myself” is a ready-made phrase. But you probably wouldn’t question my claim, and we’d probably change the subject.

Above, Orwell points out that cliches aren’t just a substitute for thinking, they’re an anesthetic. With the brain sufficiently numbed, we can be induced to accept all kinds of things.

“In our time,” Orwell writes, “it is broadly true that political writing is bad writing.” He points to ideological rebels, those writing far outside of mainstream political discourse, as possible exceptions.

Whatever their cause, whether odious or just, these political heretics aren’t compelled to spout talking points. In fact, if they want to articulate policy perspectives that few have considered, they must speak and write with some degree of originality. But “orthodoxy, of whatever colour, seems to demand a lifeless, imitative style.”

But the establishment politician is different. If any thinking happens around them, it is done by their party. The party knows what its politicians’ views are on the war in this country, on that social program, on these cultural issues. And, because politicians aren’t thinking, those who support them aren’t, either. Attend a political rally, and you’ll see another symptom of this anesthetic:

The appropriate noises are coming out of his larynx, but his brain is not involved as it would be if he were choosing his words for himself. […] And this reduced state of consciousness, if not indispensable, is at any rate favourable to political conformity.

The Defense of the Indefensible

“In our time,” Orwell writes, “political speech and writing are largely the defence of the indefensible.” In the section on pretentious diction, we saw how “political language has to consist largely of euphemism, question-begging and sheer cloudy vagueness.”

If, for example, we drone bomb a village, chasing its inhabitants from their homes and slaughtering their livestock, “this is called pacification.” If we hold people without trial in Guantanamo Bay, waterboarding them to extract information, this is called enhanced interrogation.

Toward the end of “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell invites us to imagine a professor defending the totalitarian USSR. This professor can’t say explicitly that he favors killing enemies of the party, so he resorts to euphemism:

While freely conceding that the Soviet régime exhibits certain features which the humanitarian may be inclined to deplore, we must, I think, agree that a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition is an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods, and that the rigours which the Russian people have been called upon to undergo have been amply justified in the sphere of concrete achievement.

We see, in the above paragraph, examples of each of Orwell’s “mental vices.” “Sphere of […] achievement” is a dying metaphor. Instead of saying that the Soviet government kills its opponents or sends them to labor camps, this professor employs verbal false limbs and talks about “a certain curtailment of the right to political opposition.” He’s stuffed entire paragraph with pretentious diction. The essay was written in 1948, so the USSR had been repressive for decades, and excusing their totalitarian behavior by calling it “an unavoidable concomitant of transitional periods” is defending the indefensible with meaningless words.

It’s broken, but we can fix it

In “Politics and the English Language,” Orwell isn’t unrelentingly pessimistic. The disease, he writes, is “probably curable.” If you want to help treat it, Orwell leaves us with some prescriptions.

We must, first of all, change the way our thought relates to our speech. “In prose,” he writes, “the worst thing one can do with words is surrender to them.” When you observe a concrete object—a tree, for example—you at first ” think wordlessly, and then, if you want to describe the thing you have been visualising, you probably hunt about till you find the exact words that seem to fit it.”

When we think of abstract concepts, though, “you are more inclined to use words from the start, and unless you make a conscious effort to prevent it, the existing dialect will come rushing in and do the job for you, at the expense of blurring or even changing your meaning.” Orwell thinks it may be best to delay the onrush of words as much as you can. These first words will undoubtedly be the ready-made phrases that cause so much trouble.

Instead of surrendering to the words, you can select them carefully. You can think, and and you’ll surely get closer to saying what you meant. He provides six rules that will “cover most cases”:

i. Never use a metaphor, simile or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

ii. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

iii. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

iv. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

v. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

vi. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.

These are hardly revolutionary, of course. But employing them often will no doubt help us think more clearly. If, as Orwell writes, “thought corrupts language” and “language can also corrupt thought,” then what would more refined thinking accomplish?

While we’re waiting on the end of history, it couldn’t hurt to find out.